So here we are, a few weeks into 2026, and what have I done so far? Not much, apart from working long hours in the sleet, coming home half dead, then lying in bed with the electric blanket on, drinking black Yorkshire tea [with the bag still in the mug] and reading my way through the DC Compact Comics series, eventually recovering just enough to eat crumpets and watch Seinfeld. Peaks and troughs.

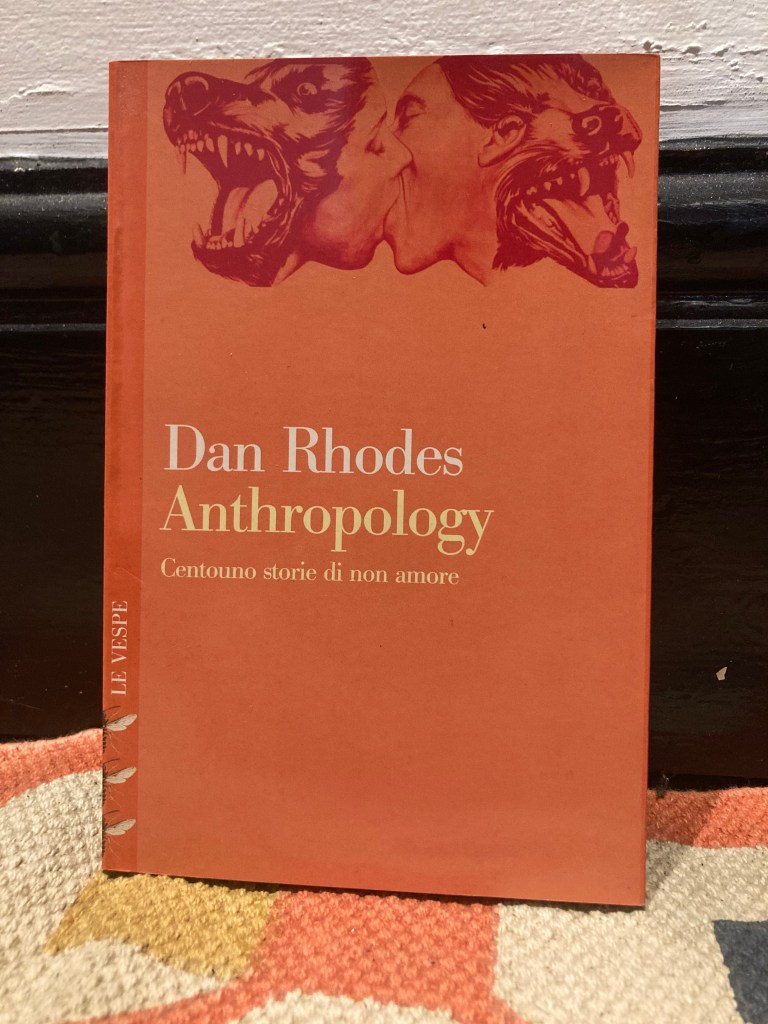

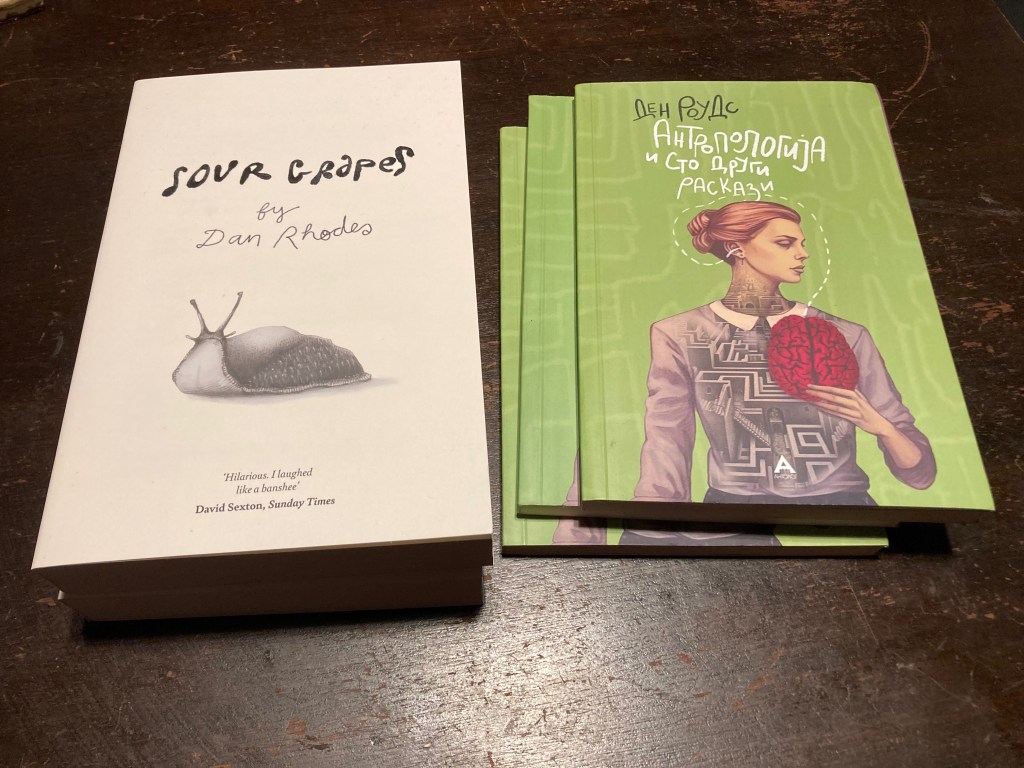

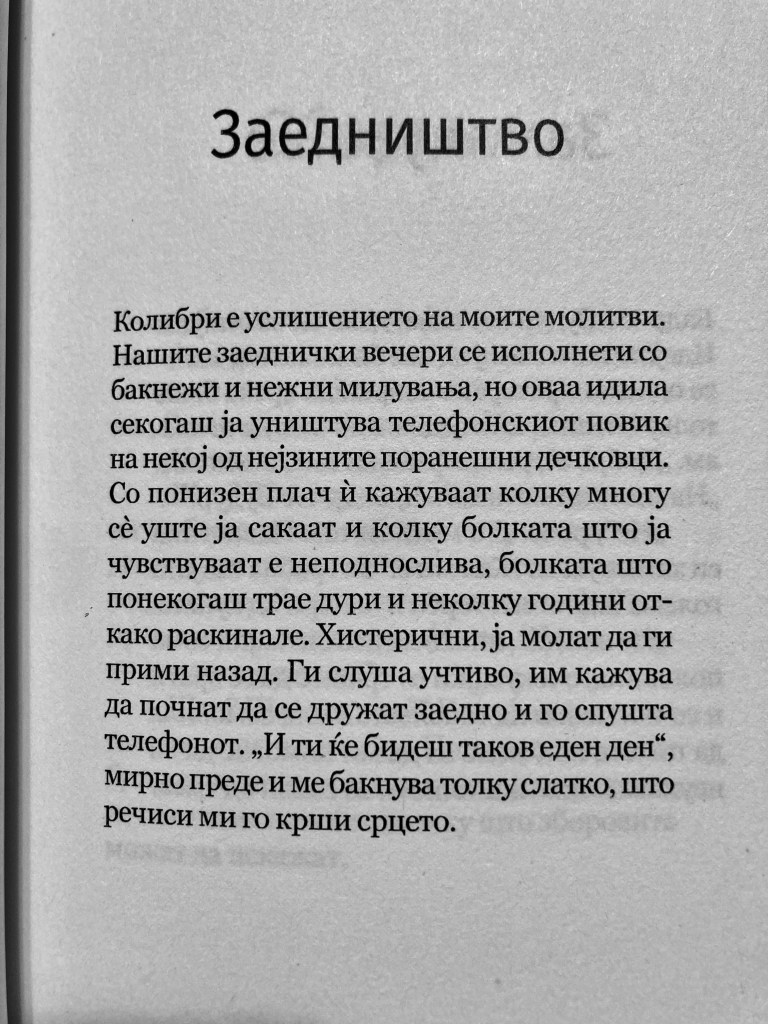

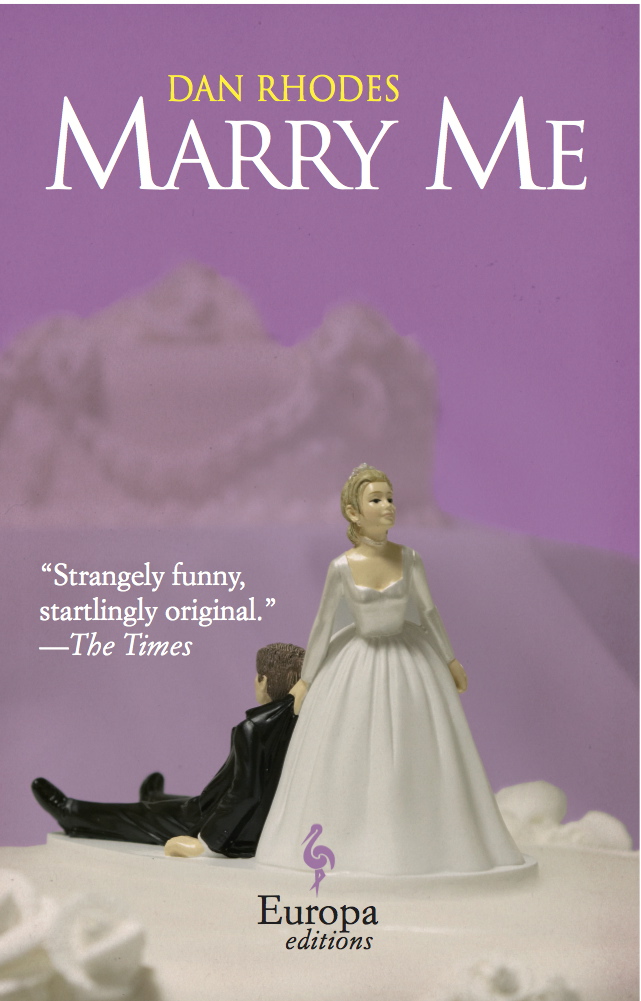

I spent much of last year’s elusive free time nailing down Tunnel of Love, Book XI in the Dan Rhodes franchise [unsurprisingly, it turned out it wasn’t nearly as ready as I thought it was when I dramatically announced its existence a year ago, and it still needed a ton of work.] It comprises my three collections of stories [Don’t Tell Me the Truth About Love, Anthropology & Marry Me], interwoven with notes that amount to a kind of meandering memoir. After more than three years of effort, it’s really ready to go this time. I’m pleased with it, and I think the new material would interest and entertain the right kind of people. You, for example. It was surprisingly enjoyable to check in with my younger self, and revisit the stories, the writing of them, and what happened next.

Regular readers of these dispatches will be wondering when the wheels are going to come off. I don’t want to keep you waiting, so here goes. [Before I proceed I would like to reassure you that I’m not going to pester you with a podcast, I don’t have a Substack (whatever that is – don’t ask me), and I don’t panhandle with Ko-fi or Patreon, or any of that. All I ask of my readers is that they read (and preferably buy) the very occasional books I put out, and indulge me by enduring these infrequent jeremiads. I consider myself to be, by today’s standards, low maintenance. Still, make yourself comfortable because this will take a while.] What follows begins on familiar ground, but a chilling turn is taken and I’ll end on a cliff-hanger.

The new material is jam-packed with behind-the-scenes industry anecdotes, of which, it turns out, I have plenty. There are gossipy stories of awkward backstage encounters with a galaxy of stars ranging from Harold Pinter to Cuddles the Monkey. Almost all the book is upbeat – call me old fashioned, but I want my readers to have a good time. That said, I’ve included a few accounts of battles I’ve fought along the way; they make up a minimal percentage of the material, but they’ve been a huge part of the story of the books, and my life, so it would be peculiar to leave them out. Missing money! Bleak corporate takeovers! Cretinous reviewers! Shitty reprints! All that dismal stuff, but told – if I’ve got it right, and I think I have – in a witty and stylish way. Not everybody is going to be happy about this – some of the people I’ll be singling out for special mention are extraordinarily vain, and in at least one case litigiously so.

As one or two of you may remember, my bête noire in the biz is the board of my former publisher Canongate Books. Batman has the Joker, Superman has Lex Luthor, you have [insert your own arch nemesis], and I have that lot. Exhausting, isn’t it? [Pocket-size summary for newcomers: they didn’t pay any royalties on my best-known book for thirteen years, insisting that nothing was amiss. This clearly wasn’t right, so I went in like a dyspeptic ferret and rooted out thousands of pounds in unpaid earnings – it turned out substantial chunks of my hard-earned cash had indeed been resting in their account. They wouldn’t acknowledge my contracts’ arbitration clauses, and they refused to get anyone in from outside to check over their records to reassure me that there hadn’t been any more bookkeeping discrepancies, peevishly demanding that I be content with them marking their own homework. I was not content. With trust in tatters, I had to pull my first eight books away from them, and they’ve been out of circulation ever since. Everything ravaged, everything burned. I went, and remain, ballistic. It was a tawdry and traumatic end to a years-long association, and the damage is ongoing. I can’t see an end to it. You are at liberty to take sides.] Naturally they feature in some of the true stories in the new book; not all of them are flattering. I’ve been careful to make sure that anything I say about them can be verified – both sides have left an amusingly comprehensive paper trail – and I can stand by every anecdote. This is old news, on its nth time around the block. However… here’s the chilling twist I promised earlier on:

Some of you may have read a recent story about them in the national press. One of their titles – a collection of light verse by Len Pennie – was the victim of a horrible review in the Sunday Times, an unseemly savaging by someone called Graeme Richardson. Critics will be critics, and sometimes they get overexcited. He ended his wretched piece by noting a close similarity between one of Len Pennie’s poems and that of another poet, Sarah Doyle. It was, sad to say, a fair point, and having spotted these likenesses it would have been odd for him to draw a veil over them. And he didn’t. Canongate Books’ response to this managed to be both pathetic and sinister at the same time: they lodged a legal complaint against the newspaper.

For a publisher that has expended a lot of bandwidth telling the world how wonderful they are, this move offered a rare glimpse of their true colours. It’s a Toytown equivalent of Trump vs. the BBC – hurling lawyers at someone who has said something you don’t want to hear, never mind that it has a solid foothold in reality. They would have had a meeting around the top table, and come to this decision together. Next time you see one of them simpering away on a book festival’s Amnesty International panel as they sound off on the importance of auctorial freedom, it might be worth raising your hand. [If you think I’m biased against them you’d be right, but you have enough key words to search for other takes on this story – it’s been widely reported and blogged about, and they’ve not found a great deal of cheerleaders. It turns out not too many people want to be seen parading around in a Make Publishing Great Again baseball cap.]

For years I’ve been like a broken record, saying that they aren’t as cute and cuddly as their PR machine would have the world believe, so it’s helpful that they’ve made my job a bit easier. It’s been a relief, and admittedly quite enjoyable, to watch people who aren’t me tearing them new arseholes for a change. I’m all in favour of literary scraps, and reviewers not having the last word [to this day Private Eye’s resident dingy double-dipper DJ Taylor can get stuffed, for example], but sending in the lawyers? No. Just no. Neither side of this dispute has covered itself in glory, but still, credit where it’s due: it takes a special talent to lose the high ground in a scrap with a Murdoch rag.

I don’t see how any self-respecting book reviewer could touch any of Canongate Books’ titles from this point on, knowing there’s a chance that the publisher will be rushing to the Inns of Justice if they decide they don’t like a perfectly valid point that had been made. You shouldn’t have to worry about the possibility of a court appearance when you’re doing a paperback round-up – how can you tell the world what you really think of the new Matt Haig when you’re staring down the barrel of a ten stretch in the slammer? I would say this amounts to intolerable working conditions, and there should be an across-the-board indefinite moratorium. [You’re right of course, there aren’t any self-respecting book reviewers, and they all hate each other so there’s no solidarity. Even if one of them was to feel a pang of conscience and turn a commission down, others would swoop in – herring gulls fighting over a dropped chip. And don’t get me started on the editors who decide who gets reviewed – those same people give full-page coverage to the serially discredited Johann Hari when they could be spotlighting reliable journalists or proper scientists. Integrity Hotel is not down at the end of New Grub Street. Everything will trundle along as if nothing has happened.]

So where does all this fit in with Tunnel of Love? In the absence of allies in the trade, my plan has been to print a short run of hardbacks – somewhere in the very low hundreds – and flog them directly to my long-suffering readers. The outlay would come out of my meagre savings, and I would need to make it back. With no economies of scale I wouldn’t be able to afford the necessary discount to get it into the shops, and even with direct selling I would have to shift pretty much all the copies to break even; if it was to turn a profit, it would be infinitesimal. A labour of love. All of which is fine – it would be reward enough to get it out there – but with enemies lurking in the long grass [a cast of characters so swivel-eyed that they set lawyers on poetry correspondents] I’m not sure I can take the risk. I can barely afford baked beans, let alone the services of a solicitor – no way could I mount a courtroom defence if they were to decide to go in heavy.

Even though they’re currently something of a laughing stock, they are still dangerous people. They’ve fired warning shots to let the world know they are ready to use the law to pick off their critics, and I’m taking this seriously – I’m gearing up to challenge them in print, and they won’t like the idea of my true stories being lodged in the British Library. Me and my book will be in their crosshairs, and it’s genuinely unnerving. This is a tiny, marginal project, but there’s no saying that would stop them. Legal letters to poetry supplements, for crying out loud. Legal letters! To poetry supplements! They’ve gone full J.D. Vance, and have access to money and lawyers in a way I don’t.

While I was writing it I felt fairly safe. After all, these are the same people who’d sent a pantechnicon full of cash – hundreds of thousands of pounds, much of it doomed – to the hideout of Julian Assange, the Whistleblower General, so they would have struggled to complain about having a whistle blown on them. Bad optics. These days, though, they don’t seem to care about bad optics. If anything, they seem to be actively pursuing the worst optics available. Perhaps they’ve decided they’ve ridden the #bekind bandwagon as far as it’ll go and it’s time for a full 180.

I don’t see why any grievances against my book wouldn’t be dismissed by any sensible judge as egregious piffle, but even so you hear horror stories about people who win legal cases but still get saddled with crippling costs. I’m not in a position to take a risk like that. If it was just me, maybe I would grasp the nettle, but other people are in harm’s way. I can’t drag my family down with me. So what to do?

I suppose I could reluctantly send them a copy, or at least the relevant passages [they don’t deserve to have the whole manuscript in their lives, and only a modest fraction of its pages concern them], and give them the opportunity to identify any objections prior to going to press. If it turned out there were any points raised where I couldn’t find the paperwork to back me up [unlikely] I could remove that particular line. But even though I have a dossier of hard evidence [which they share – it’s all based on our correspondence, as well as public domain material like their own press releases, reports in the trade press, etc.], might they still be able to insist on the removal of unflattering content, anything that is counter to their preferred narrative? In light of recent events, I wouldn’t put it past them to try. I’m really not sure how these things work.

I would, though, be prepared to offer them a right of reply, like in those documentaries about Scientology where they periodically pause the action and show a card saying something like, “The Church of Scientology gave this statement: ‘Oooh, none of this is true – we’re a proper religion, and we’re really nice, and anyone who says we’re not is lying, and we definitely don’t have our own prisons.’” I could agree to include their responses in the text. A compromise I suppose, but not without merit – the poetry fiasco has shown us that there’s enjoyment to be had in watching them slam custard pies into their own faces.

And yet… I shouldn’t have to do any of this tedious bollocks. I should be sending the book off to the printers about now, and you lot should be gearing up to have the time of your lives reading it. The serious point here is: how much of a person’s life story belongs to them, and how much of it can be commandeered and smothered by people with lots of money? I suppose we’ll find out. For the good of my health I’ve not had dealings with them for several years. Whenever I think of those people, which is many times a day, the black dog growls. The thought of being back in direct contact makes my flesh crawl, but if I’m to get this book out it looks as though I don’t have any choice.

I know I said this earlier, but it bears repeating: Tunnel of Love is not about the senior management of Canongate Books. Nowhere near – they merely pop up here and there, to be cheered or booed at the reader’s discretion. It’s about my stories – how they came to be, and the adventures and misadventures I had because of them. It is, at its heart, a romp. Considering my current mood you may not believe me, but the book contains a good deal of authentic joie de vivre. Even the dark bits will, I hope, have enough gags along the way to be a fun ride. I had a blast writing it, and I hope that shines through. Apart from some final technical nano-tweaks, I’m not going to work on the manuscript any more, no matter how tempted I may be. None of this poetry scandal business is going in, for example. It’s ready to go, and I hope you’ll get to read it before too long.

I would rather not publish it at all, though, than send it out watered down at the insistence of my antagonists. It all comes down to cold hard cash: I can’t afford to escalate this to a full-on battle, and they know it. I would have to back down at the appearance of a credible threat. I’m bracing myself for the possibility that the book won’t happen – if anything, this is the outcome I’m expecting: Prognosis Negative. Three years of work up in flames. If Dark ForcesTM put it in shackles, I expect it’ll be the end for me as a writer. Everything apart from the writing itself is such a wretched slog. If it stays in the vault I don’t see myself having enough left in the tank to keep going. It’ll be time to walk away. Morale is a factor. Exhaustion too. Time and money (lack of). Isolation in the biz takes its toll. There comes a point. If I go to ground, you’ll know what’s happened. At least I’ll have gone down fighting.

There you are. Downbeat. You can’t say I didn’t warn you. Perkier authors are available if that’s your thing. It isn’t though, is it? Good.

So it looks as though I’m going to have to send them the relevant passages. This is the cliff-hanger. You’ve probably gathered that a gauntlet is being thrown down. I’ll keep you in the loop [though don’t hold your breath – the Winter Olympics is on, and our printer’s on the blink. These things take time.] The next time I write an update it’ll either be with a spring in my step and a buy-it-now button, or plugging a crowdfunder to cover my bail.

We’ll find out together what happens next…

I hope you’re all doing well.

DR

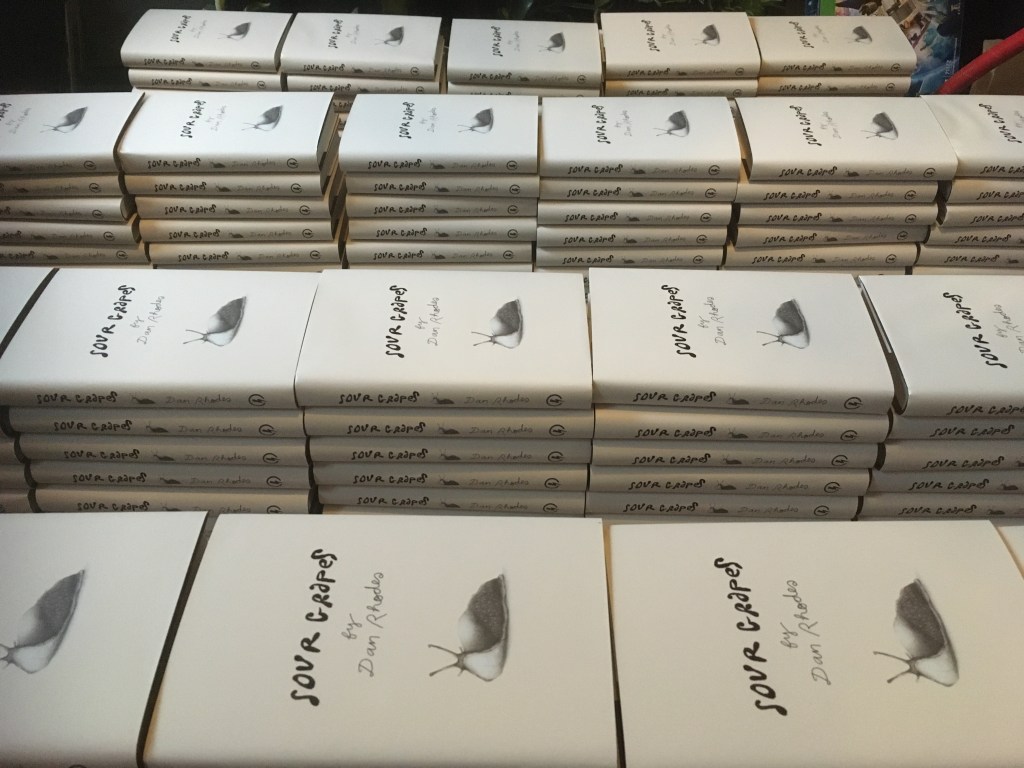

[P.S. Do yourself a favour and read Bad Traffic by Simon Lewis. As well as being the most thrilling thriller I’ve ever read, the follow-up is out any minute. Buy your copy today. My other cultural recommendation is the Beavis and Butt-Head reboot. I don’t say this lightly, but I think it’s at least as good as the first run. Start with the comeback film, Beavis and Butt-Head Do The Universe, and go from there. And if you’ve not read Sour Grapes, sort it out.]